PhotoCairo 5, a partir de 14 de Novembro

Publicado8 Nov 2012

A contemporary art project in Downtown Cairo

14 November-17 December 2012

PhotoCairo 5 is a large-scale contemporary art project organised by CIC and curated by Mia Jankowicz that explores the notion of paradigm shift.

PhotoCairo 5 is about ways in which reality is splintered and shifts of subjectivity are made. Involving international and local, emerging and established artists, this exhibition explores the ability of art to trigger affective responses within the viewer.

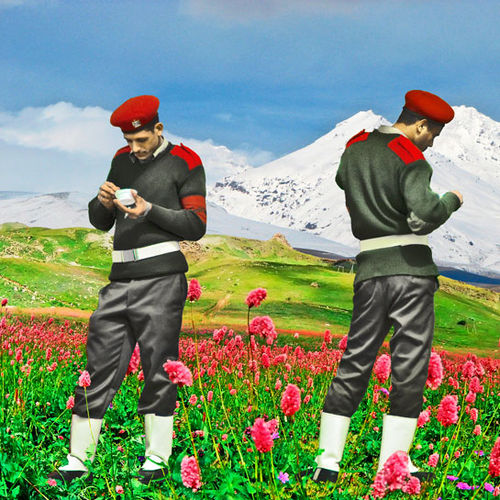

PhotoCairo 5 explores forces at play in reshaping reality, such as paranoia, the act of recognition, and altered states of consciousness. Bodies, materials and knowledges radically unreconciled to their political, architectural, institutional surroundings appear across the show: from the tale of a hysterical dancing spree near the site of the European Parliament, to an impossible monument to the revolution, and the absurd power dynamics of a re-enacted citizen's arrest gone wrong.

The project takes its title from a passing comment in Harun Farocki’s Videograms of a Revolution, in which existing footage of the Romanian Revolution of 1989 is narrated with attention to the position and motivations of the person filming. The comment refers to the decision – more out of curiosity than conviction – of a state TV camera operator to ‘glance’ the camera sideways at an emerging protest, against instructions. Farocki’s treatment of the material calls attention to this gesture over the depicted event. If art is to handle 'revolutionary acts', here the camera operator's innocent curiosity and bodily uncertainty takes the place of grand representational gestures, yet crucially, allow us to witness the awakening of a radical reality.

Click here to download PhotoCairo 5 Pocket Programme

Aqui, mais sobre o artista português André Romão, que participa nesta edição.