Memória do colonialismo na obra de Nomusa Makhubu

Publicado7 Fev 2015

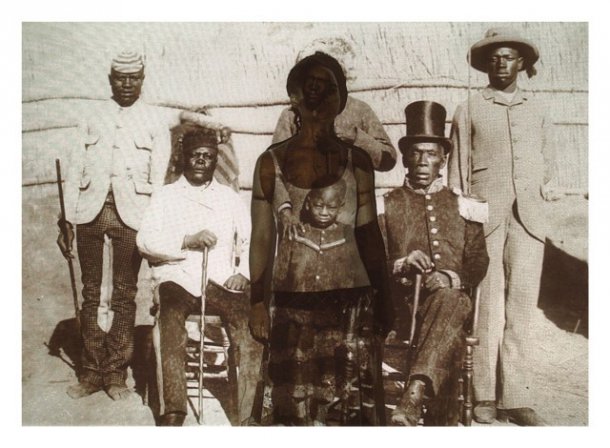

Nomusa Makhubu, nascida em 1984 na África do Sul, trabalha as questões da memória colonial,através de auto-retratos fotográficos inseridos em imagens de arquivo. Presente na Dak'Art 2014 e distinguida com Le Fresnoy Studio National des Arts Contemporains Prize, fala agora, em entrevista ao site Contemporay and, da sua obra e dos seus projectos.

CH: How did this series come about?

NM: The Self-Portrait series was originally part of a body of work and an exhibition calledPre-Served, which focused on representations of African women in colonial photography. This project represented a few challenges: the photographs themselves were problematic because they set up a clear distinction between the photographer and the photographed as male and female, European/ African, white/black – in which the former is always privileged. I wanted explore ways in which it might be possible to subvert that hierarchy, and re-write the political implications in the photograph. I asked: of what use are these photographs to contemporary politics? Of what use are tools of memory if they serve a denigrating history? Since they represent colonialism, should they simply not be erased from memory, forgotten, and delegitimized? The women in the photographs that I selected had come to represent collectivities of women and men who have been subjected to the dehumanizing scientific gaze.

CH: Importantly, the titles of these self-portraits are in Zulu, with English translations in brackets.

NM: Indeed. Titles like Mfundo, Impahla neBhayibheli [Education, Apparel, and the Bible], (2007/ 2013), Umasifanisane [Comparison] (2007/2013), and Goduka [Going/ Migrant Labourers] (2013) disturb the meta-narrative. I grew up in the industrial southern parts of Gauteng, in the Vaal Triangle, which was more socio-linguistically “mixed” by comparison to areas that were in former bantustans. I realised that when one is searching for one’s so-called identity, one begins with cultures attributed to socio-linguistic groups. I was looking for Swazi culture but I speak Zulu and thought I was Zulu. I spoke Sotho as well, having learnt it from other children around me. This project made me realise how problematic it is to consider socio-linguistic groups as autonomous cultures. I use performative photography to revise the ways in which post-memory is not only inherited memory without primary experience, but can rupture and interrogate predominantly masculine historical narratives. Performed photography, in which the archive or historical as well as canonical photographic imagery is appropriated, functions as a necessary interruption and a powerful assertion.

A entrevista completa em A disturbing memory