Egyptian Cinema Before and After the Revolution: A Conversation with Mohamed Siam

Publicado15 Jun 2012

I’m at the Cinemateca Portuguesa in Lisbon, the perfect location to web chat with Mohamed Siam, an Egyptian filmmaker and art manager involved in organizing the Egyptian Revolution.

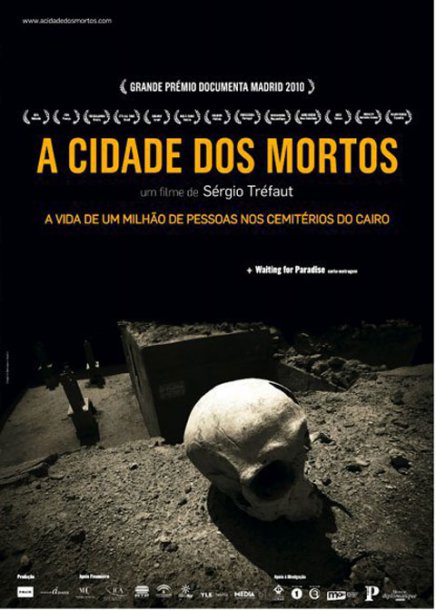

City of the Dead

Siam will be receiving an honorary degree for his role as a filmmaker from the University of San Francisco (USF). He has undergone numerous professional training courses in various areas of filmmaking, including scriptwriting, cinematography, editing and animation. He is co-founder and artistic director of Artkhana, an established film and animation space in Alexandria (Egypt). He has directed films for Softoria, a Canadian animation firm and has taught film widely, both live action and animation. He has wide experience as director, editor and cinematographer. His most recent assignment was as assistant director and local producer for a Portuguese French co-production, shot in the City of the Dead in Cairo and recently screened in Lisbon, Portugal.

He is currently filming a new feature documentary about the Egyptian revolution, to be integrated into a broader project about Arab political awakening and uprising which he will begin filming in Morocco next Summer. It deals with the concept of leadership in the Middle East and how this can eventually lead to dictatorship.

Liliana Navarra: It's very reductive to just call you a ‘film director’. You are a young artist who, in 2005, decided to create Artkhana. Can you talking about your project?

Mohamed Siam: Artkhana was someone else's initiative that I believed in and decided to push further until it was actually founded. I wanted to provide a space that I needed myself when I was my target audience's age, between 18 and 25. Since then, it has provided the opportunities to practice with, learn from, observe and interact with film and animation experts, to create this beneficial friction as early as possible in the career of local independent artists. As an artist, I work in many disciplines but my main one is cinema and, specifically, film directing. But as an auteur filmmaker, I do write, film, edit and sound design my material if I need to. My professional filmmaking experience began in 2003 and has since become intensive. I was fortunate to work with some acclaimed filmmakers in Egypt and abroad, and my network is developing to the point of involving some famous names in my future film projects.

LN: You've made several short films that hover between fiction and documentary in productions funded by, amongst others, the Anna Lindh Foundation, European Union, Jesuit Cultural Center, Pro-Helvetia and the United Nations. When did your creative adventures begin?

MS: I studied psychology and then I started working in cinema whilst studying, in 2003, by editing and assisting on films.

LN: You've just finished a short, Time Remaining (2011). What was the inspiration behind it?

MS: Memory is a great inspiring motif for me. I also feel that, as Egyptians, we are all suffering from long-term amnesia and forgetting who we are.

LN: Your film is about memory and loneliness: a man lives alone and doesn’t let other people enter his private space. Who or what inspired you to write about this condition?

MS: A friend of mine, who is like my mentor and inspiration as an artist, had the same experience of poisoning himself in one old memory for too long. He is a writer himself and he’s so interesting and dear to me that I felt I wanted to honour him with a story about memory.

LN: Last week in Lisbon, The City of the Dead (2009) by Serge Truffaut was screened, a film about the El Arafa cemetery in Cairo, which, as part of its wide festival recognition, played in the official competition in “IDFA” Amsterdam 2009 and won the Best Film Prize at Documenta Film Festival 2010. Having worked on this project, can you tell us what difficulties you and the crew encountered making it?

MS: Difficulties there were, related to convincing people we were not crazy to film their lives. My work involved casting characters, and scouting and choosing locations, so over one and a half years I maintained sustainable relationships with the people and places as the film developed over time. We were shooting without any official permits due to the maze they can get you into, without succeeding in getting proper permission to film, so it was always edgy for any officials or police to know about us, especially for the local crew. The cinematographer, Nancy, and myself, we were always threatened to be expelled from any cinema union.

LN: Do you think that the foreign gaze can falsify the reality of that place? And do you think that the documentary has a neutral gaze?

MS: I believe a foreign gaze can see beyond a local one, but the problem is the foreign portrayal of reality always depends on quick impressions and hot stories that appeal to what the west and many other civilizations want to believe about us. On the other hand, there are many profound views, such as this film has, that depend on patient observation and meaningful interaction with people and streets rather then quick, dirty, cheap journalism. We also contribute to the false image by being passive and apathetic about projecting the essence of our beautiful heritage and noble civilization.

LN: The modern atmosphere of profiteering and the heavy entertainment taxes have resulted in drastically lowering the standards of modern Egyptian cinema. Do you think that the Revolution will bring great changes in Egyptian film business?

MS: I think film producers' narrow minds have got the industry to a point where they only feed what is successful and attracts the pretentious star system. I believe that the Egyptian independent cinema now has the power to involve people in real stories and characters after the misguiding of the media institution empowered by the old repressive, corrupt regime. Now is a new era for Egyptians to see the real streets and facts. It reminds me of Neorealism in Italy after the war when there were no decent studios, and it was the birth of a new wave based on people's needs and new circumstances.

LN: What was the position of Egyptian artists before and after the Revolution? Did they have an active role?

MS: Egyptian artists were really important in the sense of street language, when we talk about the revolution. I believe some art works, like graffiti or painting on big boards to address the people in the streets, were the main clear instant message of unity and concern. For the future, for Egyptian artists, it has, at least now, become inevitable for them to avoid politics and go back to their egoist ivory towers again. Art has to be involving and sincere, otherwise it will be neglected sooner or later, and the latter is less prone to occur.

LN: Can you tell us about your next project? We know that you are directing and filming a feature documentary, Arab Modern Times, about the history of the repression before the Egyptian and Arab revolution.

MS: My next project is divided into two: a- A feature film about the Egyptian police, state security and the institutions attached to the past repressive regime; it will be seen from the angle of the police officers who did the torturing, framing people, corruption, etc. Their voices are recorded but their faces won't be shown; animation will be used to compensate and also to imagine part of the unseen incidents. It is a real document about the absence and total neglect of human rights by Egyptians, AKA proudly my people. b- A long-term film research about the awakening of Arab countries in the popular rage against the long repression from Arab leaders who took presidency as a heritage or property versus the past apathy of Arabs towards their own country, liberty and destiny.

Time is running out and we need to turn off our laptops, but we’ll keep in touch to find out about the new post-revolution Egyptian reality. What will the dictator's fall bring us?

(Lisbon/Cairo April 2011)

Lilliana Navarra

Liliana Navarra, is a PHD candidate in cinema studies at Nova Universidade in Lisbon with a project on João César Monteiro and his cinema: she is also the creator of the first official website dedicated to him, www.joaocesarmonteiro.net

She is a freelance journalist involved in media studies. She collaboreted with NapoliFilmFestival (Naples, Italy) and Indielisboa Festival (Lisbon, Portugal) and organized "O'Curto" Napolitan Film Festival (Istituto Italiano di Cultura in Lisbon, Portugal) and a retrospective "Il favoloso mondo di G" dedicated to Ugo Gregoretti's cinema (Lisbon, Portugal).