Anton Kannemeyer e Breyten Breytenbach

Publicado11 Mai 2015

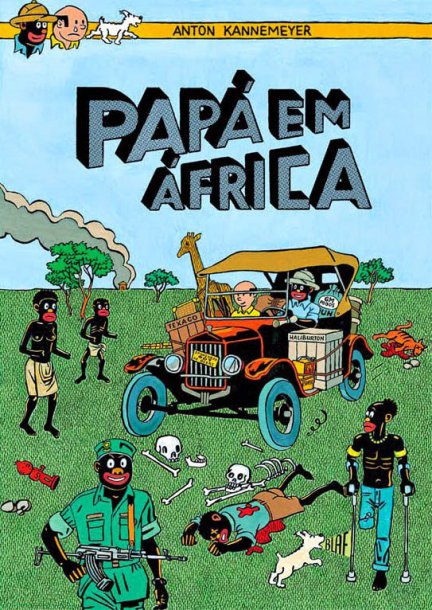

Corria o ano de 1986 quando Breyten Breytenbach, escritor que estivera preso por se opor ao regime sul-africano e que marcou presença no Próximo Futuro o Verão passado, regressou pela primeira vez à África do Sul para receber um prémio literário, cerimónia em que proferiu, mais uma vez, um discurso crítico do do apartheid, ainda a 8 anos do seu fim. Pouco depois, Anton Kannemeyer começaria o seu curso de Belas Artes e viria a tornar-se um dos grandes nomes da banda desenhada naquele país, tendo fundado, com Conrad Bates, a revista BitterComix e assinando o livro Papa em Africa (publicado em Portugal pela editora Chili com Carne), num estilo crítico e controverso que marca toda a sua obra. É na intersecção destes discursos intergeracionais de duas personalidades sul-africanas que parte Jillian Steinhauer no artigo em que analisa a obra de Anton Kannemeyer, um dos convidados da sessão do Próximo Futuro dedicado a Outras Literaturas: Banda Desenhada.

“Bitterkomix is a repository for an entire culture’s detritus,” wrote Richard Poplak in the Johannesburg Globe and Mail in 2008. “It’s where four centuries of Afrikaner history have been spat up for examination. … It is the South African subconscious.”

The magazine, which came out sporadically at first and then steadied to a yearly offering, generated considerable controversy because of its explicit sexuality and political and cultural blasphemy. Despite — or perhaps because of — this infamy, it soon gained a national following.

But the work of Kannemeyer and Botes, especially in the first ten or so years of Bitterkomix, was expressly personal, and in that certain sense, it also proved Breytenbach right: excessive self-interest implies a lack of political involvement — concern for one’s own world rather than the larger one.

While Kannemeyer’s identity as an Afrikaner necessarily gave the work political ramifications, his critique stemmed from the anxieties and trauma he experienced growing up as a member of an exploitative and racist minority ruling caste.

“Bitterkomix is a repository for an entire culture’s detritus,” wrote Richard Poplak in the Johannesburg Globe and Mail in 2008. “It’s where four centuries of Afrikaner history have been spat up for examination. … It is the South African subconscious.”

The magazine, which came out sporadically at first and then steadied to a yearly offering, generated considerable controversy because of its explicit sexuality and political and cultural blasphemy. Despite — or perhaps because of — this infamy, it soon gained a national following.

But the work of Kannemeyer and Botes, especially in the first ten or so years of Bitterkomix, was expressly personal, and in that certain sense, it also proved Breytenbach right: excessive self-interest implies a lack of political involvement — concern for one’s own world rather than the larger one.

While Kannemeyer’s identity as an Afrikaner necessarily gave the work political ramifications, his critique stemmed from the anxieties and trauma he experienced growing up as a member of an exploitative and racist minority ruling caste.

“Bitterkomix is a repository for an entire culture’s detritus,” wrote Richard Poplak in the Johannesburg Globe and Mail in 2008. “It’s where four centuries of Afrikaner history have been spat up for examination. … It is the South African subconscious.”

The magazine, which came out sporadically at first and then steadied to a yearly offering, generated considerable controversy because of its explicit sexuality and political and cultural blasphemy. Despite — or perhaps because of — this infamy, it soon gained a national following.

But the work of Kannemeyer and Botes, especially in the first ten or so years of Bitterkomix, was expressly personal, and in that certain sense, it also proved Breytenbach right: excessive self-interest implies a lack of political involvement — concern for one’s own world rather than the larger one.

While Kannemeyer’s identity as an Afrikaner necessarily gave the work political ramifications, his critique stemmed from the anxieties and trauma he experienced growing up as a member of an exploitative and racist minority ruling caste.

O artigo completo em Without Mercy: The Bitter Comix of Anton Kannemeyer