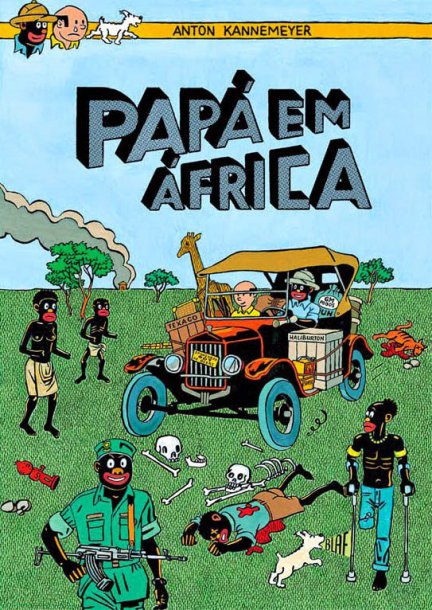

"BD & Racismo” é uma reportagem de Mário Rui Cardoso da Antena1, que entrevistou o artista sul-africano Anton Kannemeyer e o autor brasileiro Marcelo D’Salete, convidados do ciclo "Outras Literaturas: Banda Desenhada", que se realizou no passado dia 15 de Maio.

Pode ouvir a reportagem, aqui

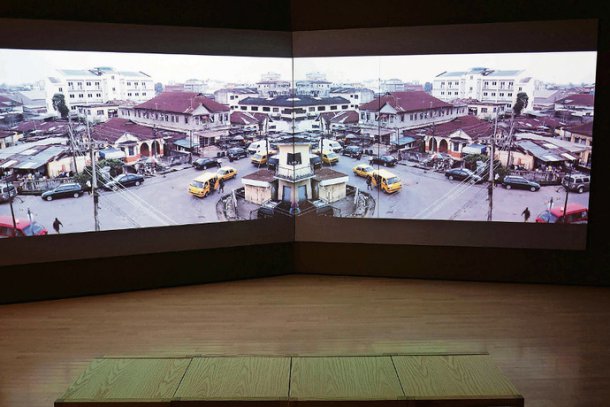

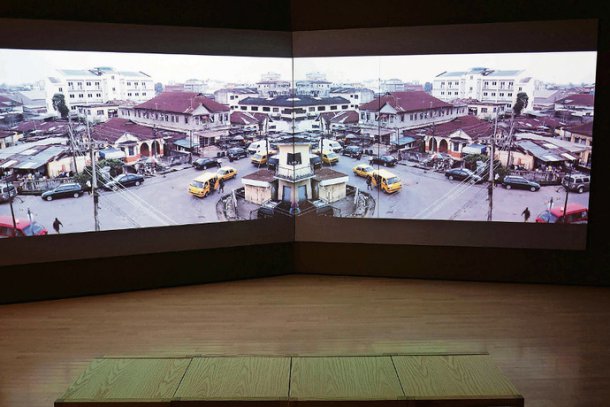

Imagem: Vídeo de Emeka Ogboh

A exposição Post African Futures apresenta, desde 21 de Maio, na Goodman Gallery, em Joanesburgo, palestras, projecções e performances no âmbito da criação digital, num continente com 280 000 utilizadores de internet, de acordo com o Internet World Stats, com a Nigeria, África do Sul e o Quénia no topo da lista da conectividade.

But who is narrating our story and creating and mapping Africa’s digital footprint?

In the creative sphere, across Africa, the narrative is already being digitally rewritten and archived by artists who have been troubled by hackneyed and problematic representations of the continent and the dangers of globalisation.

“What I attempt to do through my work and in my life is to unlearn all the nonsense I’ve been fed with growing up in the West,” says 26-year-old video artist Tabita Rezaire, who grew up in Paris but has been living in Johannesburg for the past 10 months. “I am trying to free myself (and potentially others in the process) from the spiritual, social and political oppressions of the colonial matrix of power. It is about unlinking with Eurocentrism and the pervasive hierarchy between races, genders, cultures and systems of knowledge.”

Rezaire is one of 19 artists who are showcasing their works as part of an ambitious and potentially game-changing exhibition, Post African Futures, curated by Tegan Bristow, an interactive digital media artist and head of interactive media in the digital arts division of the University of the Witwatersrand’s school of arts.

Bristow says the exhibition is an extension of her doctoral research through the United Kingdom’s University of Plymouth and came about because she was concerned about how we are “teaching European digital media and digital arts practice to students who aren’t even looking at digital media and digital art in that way at all. It’s a little destructive.

“There’s all kinds of different social political agendas around global technologies, which I think everybody in South Africa is aware of since we are specifically represented in global media in a very closed-minded way.”

O artigo completo em African digital art in the age of globalisation

Walter Mignolo, professor da Duke University, convidado das Grandes Lições do Próximo Futuro, que apresenta no próximo sábado dia 30 a conferência As mutações da colonialidade e a atual (des)ordem mundial, e um dos teóricos associados à descontrução epistemológica do pós-colonialismo com o conceito de colonialidade/de-colonialidade, deu uma entrevista ao site Contemporay and onde fala da questão da "estética descolonial".

C&: Decolonial aesthetics is a concept you have developed in the process of your reflections and work. How did this come about?

Walter Mignolo: First of all, this one, as any concept of the modernity/coloniality/decoloniality collective project, is a consequence of collective conversations. It was introduced in the conversation by Adolfo Alban Achinte, perhaps toward 2003, when he was still a PhD candidate at the Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar in Quito, Ecuador. It came out of conversations on the colonial matrix of power: what is the place of aesthetics in the colonial matrix? We have been talking about coloniality of knowledge and coloniality of being, political and economic coloniality, or coloniality of religion trapping spirituality, coloniality of gender and sexuality, coloniality of ethnicity (from which racism sprung). But we had not yet touched aesthetics. And the reason was that none of us up to that point were artists or art historians or art critics. But Adolfo was, being an artist and activist, from the Colombian Pacific, Afro-Colombian.

It was in the summer of 2009 that the issue exploded. At that point Adolfo was already the assistant to the director of the program, Catherine Walsh. I have been a professor and collaborator of Catherine Walsh since the beginning of the PhD program. Pedro Pablo Gómez, from the School of Fine Arts in Bogotá, was working on his PhD but was also the general editor of a new publication, CALLE 14. revista de investigacion en el campo del arte (“STREET 14. journal of investigation in the field of art”). He invited me to write an article for the journal. The article “Aesthesis Decolonial” was published in March of 2010. But, while the article was in production (I finished it in the fall of 2009) Pedro Pablo suggested to co-curate an exhibit-cum-workshop with the title “Estéticas Descoloniales” (“Decolonial Aesthetics”). The subtitle became, in the process “Sentir, pensar y hacer en Abya-Yala” (“Sensing, thinking,g and doing in Abya Yala”). We emphasized “sensing, thinking and doing”, breaking away from the European eighteenth-century distinction and hierarchy between “knowing, rationality” and “sensing, emotions.” Meanwhile, Adolfo was in Argentina participating in a workshop organized by Zulma Palermo, in Salta, a member of the collective. Zulma was also working with some of her colleagues and students on the question of an aesthetics/aesthesis.

DECOLONIAL AESTHETICS/AESTHESIS HAS BECOME A CONNECTOR ACROSS THE CONTINENTS”

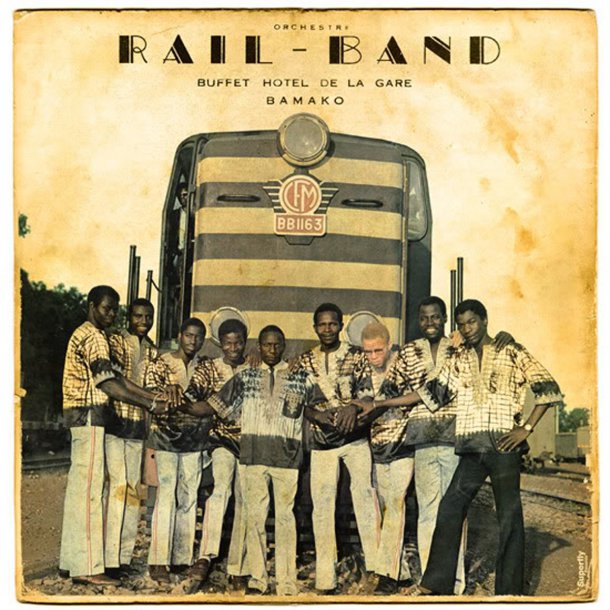

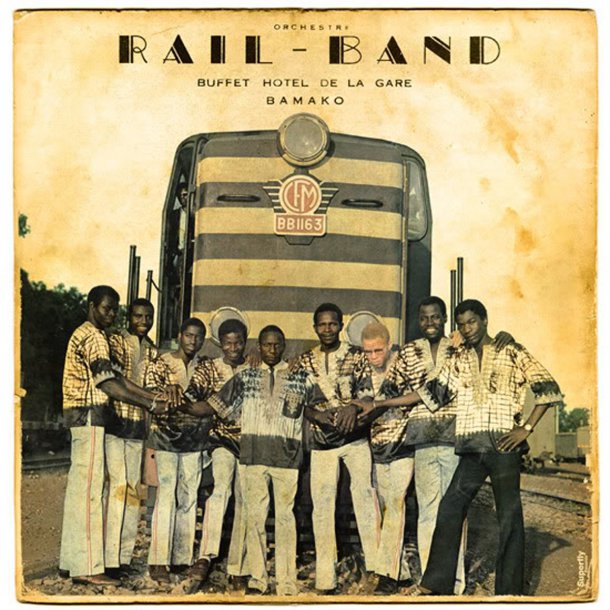

As independências dos países africanos dos países colonizadores europeus provocaram uma eferverscência cultural naqueles países. O site Afribuku analisa o caso do Mali, na música, e história da Orquestra do Mali.

A finales de los años 50, con la llegada de las primeras independencias, surge una verdadera revolución cultural que busca recuperar la identidad del rico legado histórico que durante el paréntesis colonial se les negó una y otra vez a los pueblos africanos. Estas independencias traen consigo vitalidad, progreso y esperanza; y las artes, como medios de expresión, viven años de gran creatividad y fertilidad. La música fue uno de los pilares de esta revolución. Las bandas de jazz que amenizaban las soeirées africanas de las clases bien estantes durante la colonización se popularizan y empiezan a recuperar parte del rico folklore tradicional que se fusiona con los nuevos ritmos. Malí es un claro ejemplo de este reencuentro entre modernidad y tradición, situado en pleno corazón del Sahel, la música y tradición oral han recaído a lo largo de su historia en manos de los Griots. Estos como poseedores de la palabra y del verbo han sido y son los encargados de transmitir el conocimiento entre generaciones y de hacer que este país sea uno de los más fértiles en tradición musical. Los 75 años de colonización francesa no fueron suficientes para hacer desaparecer el rico legado cultural heredado del antiguo imperio maliense (1235-1546).

Su independencia llega el 22 de septiembre de 1960 con Modibo Keita como primer presidente de la República de Malí. Este tiene una clara voluntad política de recuperar la “autenticidad cultural africana” siguiendo el referente de las políticas africanistas de la vecina Guinea de Sékou Touré o la Ghana deNkrumah. Tanto es así que al día siguiente a la independencia el Gobierno crea la Orchestre National du Malí para reunir en ella a los principales músicos del país que, como funcionarios del estado, pasan a ser encargados de recuperar el diverso folklore tradicional, modernizarlo y popularizarlo con el fin de transmitir al pueblo la “autenticidad africana”. Además de la Orchestre National du Malí, dirigida por el balafonista y guitarra solista Kélégueti Diabaté, también se crean las formaciones B y C de esta misma orquesta. El gobierno de Keïta funda l’Ensamble Instrumental National du Mali dirigida en sus orígenes por N’Fa Bourama Sacko y en 1962 organiza la primera Semaine Nationale de la Jeunesseque servirá en sus distintas ediciones como aparador de la diversidad de expresiones culturales del país.

Los sonidos de las independencias: Orquestas de Malí

(Imagem do site http://www.flf.co.za/)

O Franschhoek Literary Festival aconteceu dias 15, 16 e 17 de Maio, na África do Sul, um evento que se organiza desde 2007 naquela localidade. O New York Times publica um artigo sobre o festival, analisando as tensões que o atravessam.

Franschhoek, about an hour’s drive from Cape Town, means “French corner” in Dutch; its name derives from the 200-odd Huguenot settlers who, fleeing religious persecution in their home country, came to South Africa in 1688 and began to produce wine in this lush valley ringed by mountains. Today, the town’s startling natural beauty, well-preserved Cape Dutch architecture, and many vineyards and restaurants have turned it into a major tourist destination.

In 2007, a small group of enthusiasts started a literary festival as a way to raise money for a local library. Today it is a major event on the South African cultural calendar. Audiences, some 5,000 this year, many from other parts of the country, crowd into the tiny town to attend three days of tightly packed discussions, book releases and concerts.

But as Mr. Madondo, who is black and is the author of a book on the singer Brenda Fassie, pointed out, the festivalgoers are mostly white — a curious and pertinent index to the difficulties and ambiguities around race, class and culture that still permeate South African society, where whites make up just 8.4 percent of the country’s population, estimated at 54 million last year.

The festival doesn’t shy away from exploring these difficulties. The program, while containing a fair share of literary topics, is far more oriented toward socio-cultural or socio-political topics than most events of this kind. Subjects like “Fear and Loathing in South Africa”; “What Makes One an African?”; “Can the A.N.C. be Mended?” and “We Won’t Get No Education” make up about half of the events, and the panels are generally models of racial diversity.

“The topics about politics and social issues are our biggest events and always sold out,” said Ann Donald, the director of the festival, who is white. “I think South Africans are trying to understand their situation, whatever capacity they are coming from.”

O artigo completo em At South African Literary Festival, Broaching Uncomfortable Subjects

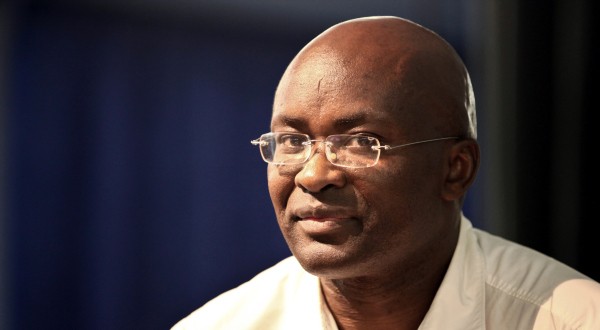

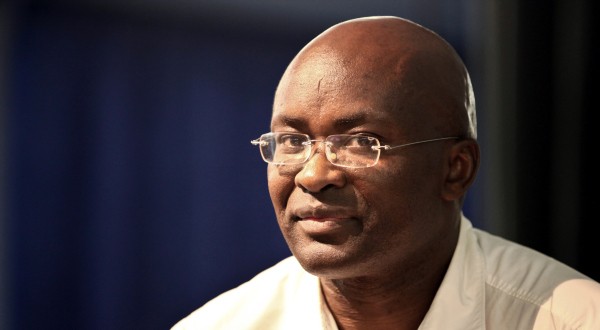

Okwui Enwezor. PHOTO: ACTION PRESS/ZUMA PRESS

O nigeriano Okwui Enwezor, o primeiro africano à frente da Bienal de Veneza, em entrevista ao The Wall Street Journal, explica as suas opções para a 56ª edição, sob o mote “All the World’s Futures".

Mr. Enwezor titled this year’s exhibition “All the World’s Futures,” reflecting his interest in a wide range of media—from a nonstop reading of all three volumes of Karl Marx’s “Das Kapital” by a group of actors to a copper dome that Congolese artist Sammy Baloji built to criticize Belgium’s exploitation of Congolese copper mines.

With a budget of roughly $15 million supported by private funding, Mr. Enwezor has also created a section called Arena, designed to showcase performance works dealing with difficult themes that he hopes will make their way into mainstream art. “I have the freedom to make proposals that might ultimately fail on a commercial level,” he says.

One such initiative is the Invisible Borders Trans-African Project. These little-known African artists have road-tripped together across Africa since 2009, making the type of cultural exchanges taken for granted at U.S. and European art schools.

O texto completo em New Venice Biennale Chief Beckons Artists on the Margins

Délio Jasse, artista angolano nascido em 1980, que teve obra exposta no âmbito do Próximo Futuro em 2011, e que integra em 2015 o Pavilhão de Angola da 56ª Bienal de Veneza, deu uma entrevista agora publicada no site Art South Africa.

What led you to photography?

I fell in love with photography after working in a screen- printing atelier. There was a photography studio within the atelier, where we created photoliths by separating the colours. I’ve been a fan ever since.

So would you say that your work is photographically inspired?

I am inspired by the notion of experimenting with photography, but as you can see, my interaction with photography is not conventional. By layering and superimposing my images, I lessen the depth of field that is commonly associated with photography. So yes, to answer your question I would say that I am photographically inspired, even though I would not label my work as purely photographic. Although it is essential to my work — being the starting point of my experimentation — it is not the cornerstone of my speech.

Are there any African photographers that inspire you?

I don’t really have an “African” inspiration, even though there are many African artists whom I admire and respect. I admire artists who are unafraid of experimenting with the different options offered by the photographic medium.

How do you feel about the statement "Everybody is a photographer?"

I believe that as long as we have the ability to see, we have the ability to reproduce it as an artform.

Snapped in Conversation with Délio Jasse

Imagem: Wura-Natasha Ogunji, beauty, 2013. Photo: Soibifaa Dokubo

Wura-Natasha Ogunji é uma artista nigeriana, fotógrafa, performer, professora e antropóloga. Inquieta com a escassez de imagens da negritude a História da fotografia, iniciou uma série de auto-retratos num processo de busca identitária relacionada com a noção de memória e ancestralidade. Em entrevista ao site Contemporary And, a artista fala do seu percurso e obra.

C&: How is the notion of (collective) memory in relation to the body (being physical, social, etc.) important to you?

WNO: Our bodies are such great containers of memory. And our consciousness holds so much information about our histories, even our futures. Scientifically speaking, we’re carrying this genetic material that is millions of years old. These bodies know a lot and tell a lot. I love how performance taps into this information; I love what it pulls out and where it can take us.

C&: We were recently asked by a journalist why we think global art tends more and more to look the same. You can’t look at a work from Nigeria any longer and say, hah!, that’s Nigerian. What do you think about that development?

WNO: To say that global art looks more and more the same is to miss out on the innovative ways in which artists are working today, and it also misses the nuances and specificity of place and experience. I think the more exciting and important questions have to do with the changing ways we create, as well as write about, talk about, curate, teach, and experience art in this historical moment. The range and diversity of art practice today, naturally, moves beyond and across geographic boundaries. Artists have totally expanded the landscape for making and sharing their work, so the language that we use to understand this work must also shift.

A entrevista completa, aqui

Imagem: José Fernandes

A escritora sul-africana Lauren Beukes esteve no Próximo Futuro no passado fim-de-semana, no encontro Outras Literaturas: Policial. Numa entrevista ao Jornal I, a autora fala sobre o livro Raparigas Cintilantes (Porto Editora) e as ideias que moldam a sua criação.

Este livro centra-se na história de um serial killer que viaja no tempo e na das suas vítimas, em particular naquela que lhe sobrevive. Como surgiu a ideia de juntar crimes e viagens no tempo?

Achei que era uma boa ideia e uma boa forma de jogar com as convenções deste género literário, porque, genericamente, não gosto da narrativa dos homicídios em série. Na cultura pop glorificam-se os serial killers. Se olharmos para séries de televisão como o “Hannibal”, eles são génios intrigantes e diabólicos, como se fossem supra-humanos, monstros. E não são. É interessante que está a decorrer aqui [na Gulbenkian], a conferência “Vítimas de Crime na Europa”. E o que é a violência na Europa? Acabamos por chegar à violência doméstica. E esse é o real perigo que existe no mundo, a violência doméstica, não são os serial killers. Estes são apenas um aspecto do problema.

Como são então?

São homens desprezíveis que fazem coisas horríveis, porque é a única linguagem que sabem usar para se expressar. Há qualquer coisa neles que está quebrada e danificada mas eles não são interessantes. E quando se vêem entrevistas reais percebe-se que eles não têm razões plausíveis. Os seus parentes não foram comidos por canibais numa floresta russa, como na história de Hannibal Lecter. Por isso quis falar mais das vítimas do que do assassino. E a viagem no tempo permitiu-me perverter a realidade e ao mesmo tempo conseguir aproximar-me dela.

A entrevista completa, aqui

Achille Mbembe, cientista político e filósofo, autor de Sortir de la grande nuit – Essai sur l'Afrique décolonisée e Critique de la raison nègre (publicada em Portugal como Crítica da Razão Negra) deu um conjunto de palestras públicas no Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research (WISER), University of the Witwatersrand (Johannesburg), escritas num registo oralizante, como se esclarece num preâmbulo ao artigo que aqui partilhamos, que se debruça sobre as recentes tensões raciais na África do Sul.

Twenty one years after freedom, we have now fully entered what looks like a negative moment. This is a moment most African postcolonial societies have experienced. Like theirs in the late 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, ours is gray and almost murky. It lacks clarity.

Today many want to finally bring white supremacy to its knees. But the same seem to go missing when it comes to publically condemning the extra-judicial executions of fellow Africans on the streets of our cities and in our townships. As Fanon intimated, they see no contradiction between wanting to topple white supremacy and being anti-racist while succumbing to the sirens of isolationism and national-chauvinism.

Many still consider whites as “settlers” who, once in a while, will attempt to masquerade as “natives.” And yet, with the advent of democracy and the new constitutional State, there are no longer settlers or natives. There are only citizens. If we repudiate democracy, what will we replace it with?

O artigo completo, aqui

Fábio Fernandes (Brasil) é um dos convidados do encontro "Outras Literaturas: Ficção Científica". Autor do livro Os Dias da Peste, uma ficção científica cyberpunk ambientada no Rio de Janeiro, é também professor de cursos de Jogos Digitais. Numa oficina literária, em Seattle, conheceu Neil Gaiman, autor de novelas gráficas e criador da personagem Sandman.

Sobre a oficina literária nos Estados Unidos, Fábio comenta: “É importante ressaltar que Gaiman foi apenas um de seis incríveis escritores e editores que ensinaram a 18 escritores iniciantes no mercado anglo-americano como escrever melhor e publicar seu trabalho nesse mercado”. Porém, além de ter aulas com Neil Gaiman, o professor da PUC teve a oportunidade de passar 30 minutos a sós com o roteirista que inspirou uma geração de fãs de quadrinhos adultos da Vertigo, selo da DC Comics, mesma criadora de Superman e Batman.

“Neil Gaiman foi extremamente generoso e me perguntou o que eu desejava aprender, além de apontar em um de meus contos as qualidades e defeitos, e o que eu poderia fazer para me tornar um escritor melhor. Isso é muito melhor do que uma foto ou um autógrafo”, disse o brasileiro. E ele completou, sobre o encontro: “Uma das maiores lições que ficaram de Gaiman para mim é que, com dedicação e concentração, você pode escrever o que quiser”.

O professor da PUC afirmou também ter certeza de que o criador de Sandman terá sucesso com seu game na indústria de jogos. “Não tenho dúvidas de que ele poderá contribuir com excelentes narrativas não-lineares, trabalhando mitos e lendas nos jogos, que são seus temas preferidos”. Neil Gaiman, escritor de quadrinhos como “Sandman” e “Coraline”, além do livro “Deuses Americanos”, anunciou em julho deste ano a produção de um game para PC, Mac e tablets chamado “Wayward Manor”, unindo o sobrenatural com o humor.

O artigo completo em Brasileiro recebe dicas de Neil Gaiman para dar aulas sobre roteiro de games

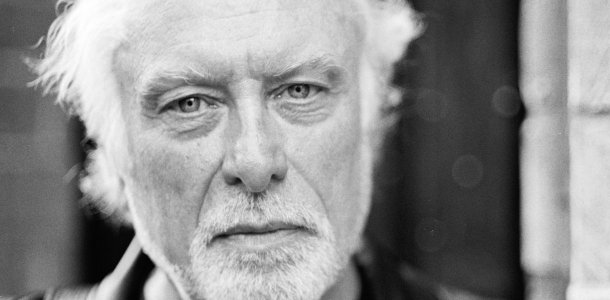

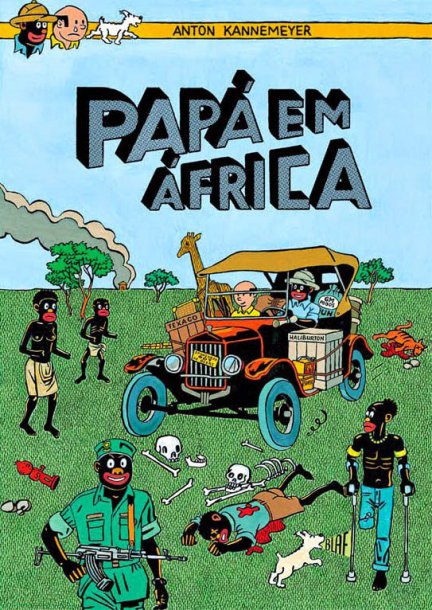

Corria o ano de 1986 quando Breyten Breytenbach, escritor que estivera preso por se opor ao regime sul-africano e que marcou presença no Próximo Futuro o Verão passado, regressou pela primeira vez à África do Sul para receber um prémio literário, cerimónia em que proferiu, mais uma vez, um discurso crítico do do apartheid, ainda a 8 anos do seu fim. Pouco depois, Anton Kannemeyer começaria o seu curso de Belas Artes e viria a tornar-se um dos grandes nomes da banda desenhada naquele país, tendo fundado, com Conrad Bates, a revista BitterComix e assinando o livro Papa em Africa (publicado em Portugal pela editora Chili com Carne), num estilo crítico e controverso que marca toda a sua obra. É na intersecção destes discursos intergeracionais de duas personalidades sul-africanas que parte Jillian Steinhauer no artigo em que analisa a obra de Anton Kannemeyer, um dos convidados da sessão do Próximo Futuro dedicado a Outras Literaturas: Banda Desenhada.

“Bitterkomix is a repository for an entire culture’s detritus,” wrote Richard Poplak in the Johannesburg Globe and Mail in 2008. “It’s where four centuries of Afrikaner history have been spat up for examination. … It is the South African subconscious.”

The magazine, which came out sporadically at first and then steadied to a yearly offering, generated considerable controversy because of its explicit sexuality and political and cultural blasphemy. Despite — or perhaps because of — this infamy, it soon gained a national following.

But the work of Kannemeyer and Botes, especially in the first ten or so years of Bitterkomix, was expressly personal, and in that certain sense, it also proved Breytenbach right: excessive self-interest implies a lack of political involvement — concern for one’s own world rather than the larger one.

While Kannemeyer’s identity as an Afrikaner necessarily gave the work political ramifications, his critique stemmed from the anxieties and trauma he experienced growing up as a member of an exploitative and racist minority ruling caste.

“Bitterkomix is a repository for an entire culture’s detritus,” wrote Richard Poplak in the Johannesburg Globe and Mail in 2008. “It’s where four centuries of Afrikaner history have been spat up for examination. … It is the South African subconscious.”

The magazine, which came out sporadically at first and then steadied to a yearly offering, generated considerable controversy because of its explicit sexuality and political and cultural blasphemy. Despite — or perhaps because of — this infamy, it soon gained a national following.

But the work of Kannemeyer and Botes, especially in the first ten or so years of Bitterkomix, was expressly personal, and in that certain sense, it also proved Breytenbach right: excessive self-interest implies a lack of political involvement — concern for one’s own world rather than the larger one.

While Kannemeyer’s identity as an Afrikaner necessarily gave the work political ramifications, his critique stemmed from the anxieties and trauma he experienced growing up as a member of an exploitative and racist minority ruling caste.

“Bitterkomix is a repository for an entire culture’s detritus,” wrote Richard Poplak in the Johannesburg Globe and Mail in 2008. “It’s where four centuries of Afrikaner history have been spat up for examination. … It is the South African subconscious.”

The magazine, which came out sporadically at first and then steadied to a yearly offering, generated considerable controversy because of its explicit sexuality and political and cultural blasphemy. Despite — or perhaps because of — this infamy, it soon gained a national following.

But the work of Kannemeyer and Botes, especially in the first ten or so years of Bitterkomix, was expressly personal, and in that certain sense, it also proved Breytenbach right: excessive self-interest implies a lack of political involvement — concern for one’s own world rather than the larger one.

While Kannemeyer’s identity as an Afrikaner necessarily gave the work political ramifications, his critique stemmed from the anxieties and trauma he experienced growing up as a member of an exploitative and racist minority ruling caste.

O artigo completo em Without Mercy: The Bitter Comix of Anton Kannemeyer

Oreo, de Fran Ross, de 1974, é um romance satirico e bem humorado, que conta a história de uma rapariga, filha de pai judeu e mãe negra, que cresce com os avós e que na adolescência resolve procurar o pai. O livro passou espercebido na época da sua primeira edição e ganha hoje novas leituras, à luz das questões identitárias, a nível étnico e cultural. Na New Yorker, Danzy Senna compara-a com outras narrativas relacionadas com a identidade:

The titles themselves of these two texts—“Roots” and “Oreo”—imply the profound gap between the works, giving us a clue about the kind of black narratives we like to celebrate, and the kind we’ve tended to ignore. “Roots” looks toward the past. It offers black people an origin story, an imagined moment of racial purity—when the Mandinka warrior Kunta Kinte is kidnapped, off the shores of Gambia. It constructs a lost utopia for us and a clear fall from the Eden of Africa. “Oreo,” from the title alone and its first loony pages, suggests murkier, more polluted racial waters.

Indeed, Oreo’s origin story is one of gleeful miscegenation. The moment Samuel Schwartz falls for Helen (Honeychile) Clark, it’s too late to look back. An “oreo” is, of course, not simply a black-and-white cookie but also the standard taunt directed at black people who appear to “act white.” Ross embraces this epithet, embraces the idea of falling from racial grace. But it’s no mulatto sentimentalism, no simplistic “ebony and ivory” tale of racial mushiness. From page one, both sides of Oreo’s family—the black and the Jewish—are equally horrified by their children falling in love. In fact, James Clark, Helen’s father, Oreo’s black grandfather, is so horrified by his daughter’s coupling with a Jewish guy that his actual body becomes encoded by hate—paralyzed into the shape of a half-swastika.Oreo, born Christine Clark, the biracial progeny of the fall, is our heroine, and, like all good heroes and heroines, she’s on a quest. But, unlike Alex Haley, Oreo is trying to find her white side—her missing Jewish father. Her absent father is no site of longing; he’s a voice-over actor in Manhattan, who has left her an absurd list of clues to help locate him. He’s a bum, according to her mother. “I’m going to find that fucker” is how Oreo sets out on her search, which feels more like an excuse to wander away from her home than a real desire for a father.

O artigo completo em Shades of Blackness

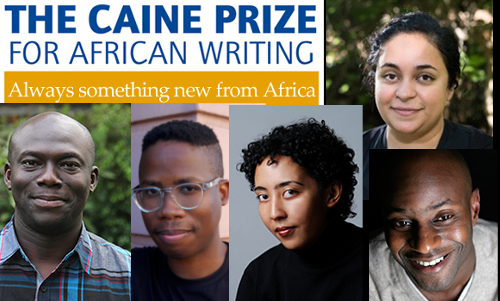

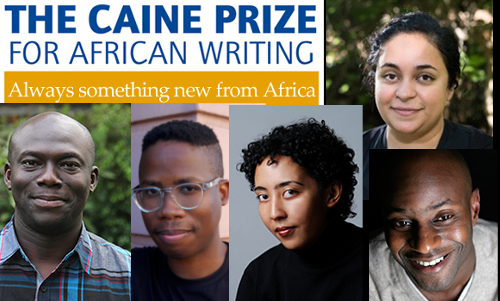

Foram anunciados os finalistas do Caine Prize For African Writing, um prémio destinado a premiar nomes emergentes e que, indo já na sua décima sexta edição, tem sido alvo de algumas críticas.

Sin embargo, el anuncio de esta lista de finalistas suscita aplausos y abucheos. Por un lado, los cinco aspirantes ponen de manifiesto que la literatura africana goza de buena salud y que tiene un próspero futuro garantizado. Por otro, los responsables del premio no han superado algunas de las críticas que se les han planteado en las últimas ediciones, como la preeminencia de escritores de origen africano que escriben desde el extranjero o un cierto vicio de regencia de la literatura africana por parte de organizaciones del norte.

Una de las novedades de esta edición es lo que los responsables del premio consideran una muestra de madurez del premio. Ha llegado a su decimosexta edición por lo que no era de extrañar lo que ha ocurrido. La lista incluye a un escritor que ya ha ganado en una ocasión el premio y a otro más que en ediciones anteriores también fue preseleccionado.

Los autores de los relatos seleccionados son los nigerianos Segun Afolabi y Elnathan John, los sudafricanos FT Kola y Masande Ntshanga y la zambiana Namwali Serpell. Tres hombres y dos mujeres. Pero la mayoría de ellos asiduos de los premios internacionales y de las becas para escritores. El nombre más desconocido de esta nómina es el de la sudafricana FT Kola, cuya única historia publicada es precisamente la que le ha valido esta preselección “A Party for the Colonel”, editada en diciembre de 2014 por la revista neoyorkina One Story.

O artigo completo em Caras y cruces en el Caine Prize

Sin embargo, los otros autores tienen ya una amplia experiencia en lides como la de la lista de finalistas del Caine Prize. Sin ir más lejos, el nigeriano Segun Afolabi ya fue galardonado con este mismo reconocimiento en 2005, por su relato “Monday Morning” publicada en la revista británica Wasafiri. A partir de ese momento, el escritor publicó su primer libro, una antología de relatos breves titulada A Life Elsewhere y después su primera novela, Goodbye Lucille. El primero de los trabajos apareció en la lista de finalistas de la premio para escritores de la Commonwealth y el segundo, recibió el Authors’ Club Best First Novel Award. Uno de los temas preferidos del autor es el desarraigo y para ello coloca a sus personajes en entornos que les son ajenos, una especie de ejercicio de descontextualización que enfrentan a sus protagonistas a la soledad, la nostalgia o la pérdida.

“The Folded Leaf” de Segun Afolabi

“Flying” de Elnathan John.

“A Party for the Colonel” de F. T. Kola.

“Space” de Masande Ntshanga.

“The Sack” de Namwali Serpell.

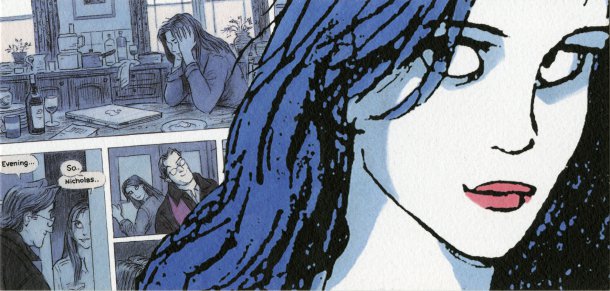

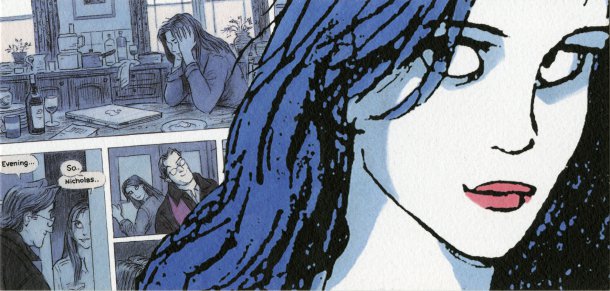

Posy Simmonds é uma das convidadas do encontro do Próximo Futuro "Outras Literaturas: Banda Desenhada" no próximo dia 15 de Maio, na Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. Um dos nomes mais aclamados de novelas gráficas, assinou Gemma Bovery (1999) e Tamara Drewe (2006), esta última distinguida em 2008 com o Essentiel d’Angoulême, o Prix des Critiques e uma nomeação para o Eisner Award. Ambas as novelas gráficas foram adaptadas ao cinema. Pedro Moura, moderador da sessão, escreve sobre a autora e Tamara Drew, no blogue Ler BD:

Este livro, de banda desenhada, para além das naturais cenas, isto é, os eventos representados nas mais normalizadas estratégias da banda desenhada (imagem), apresenta ainda trechos de texto (recitativos) assaz longos, como se tivessem sido retirados de um diário, de um longo pensamento como acontece nos textos literários, ou de um momento de interlocução directa com as personagens do livro, inseridos nas pranchas. Essa é uma das características do trabalho de Simmonds já presente no livro anterior, Gemma Bovery, característica que coloca estes livros num campo entre o da banda desenhada e o da literatura, quer a ilustrada quer atout court. Não acontece o mesmo que em Hugo Cabret de Selznik, onde a estranheza é mais complexa; digamos que há uma maior inércia em incluirTamara Drewe na banda desenhada ainda que existam estas estratégias algo estranhas – mas não inéditas, pois basta pensar na história desta linguagem para nos apercebemos que nem sempre a banda desenhada seguiu a mesma maneira de transmitir a parte textual, com legendas minimizadas e balões, mas empregando grandes blocos de texto “externo” à imagem.

Se Gemma Bovery estabelecia laços estreitos e a vários níveis com Madame Bovary, de Flaubert, Tamara Drewe acaba por se revelar como tendo afinidade com outros universos ficcionais, mas Far from the Madding Crowd, de Thomas Hardy, é, poder-se-á dizer, a fonte explícita deste livro: é a primeira informação textual que se lê no interior do texto, tratando-se do título do anúncio do retiro de escritores, no campo, em torno do qual toda a acção se desenha; a trama desse romance é em tudo idêntica, ainda que nos seus mais gerais contornos, com a desta banda desenhada – a chegada de uma mulher jovem, cosmopolita e sedutora, estranha àquela vila, seduzindo o jovem rural que é menos polido nos negócios do amor; seduzindo outros homens e instigando contínuas atribulações entre rivais; a “pintura”, como se costuma dizer, da vida rural mas revelando o seu aspecto mais prosaico e até violento em vez de o empregar enquanto paisagem bucólica; a típica tensão entre as pulsões do amor e da morte... É como se Posy Simmonds escolhesse – e não o escondesse, mais, o revelasse mesmo, tornando-se parte do jogo intertextual explícito – uma obra de literatura conhecida, a reduzisse à sua estrutura actancial (à la Greimas) e depois a preenchesse com novos elementos, mais próximos da experiência contemporânea, quer em termos civilizacionais quer em termos sociais, para nos ofertar uma nova versão dessa antiga história. Desse modo, revela aquela ideia feita de que um clássico é sempre legível de novo de um novo modo, e de que existem estruturas ou ideias que podem ser repetidas porque farão parte intrínseca da experiência humana. Por outro lado, as semelhanças entre Bovery e Drewe são em termos de estilo, o que não poderá constituir matéria nem de surpresa nem de desagrado.

O texto completo, aqui

Claudia Piñeiro é uma das convidadas do encontro do Próximo Futuro dedicado à Literatura Policial, que acontece já no próximo dia 16 de Maio. A autora argentina, que assinou“Las viudas de los jueves” e "Una suerte pequeña”, deu recentemente uma entrevista à Revista "N" da Clarín

La muerte la persigue. Aunque no quiera o jure que se le cruza sin premeditación ni alevosía, a Claudia Piñeiro la muerte le tira. Se le impone en sus ficciones, pero también en la vida real, como cuando en octubre del año pasado un delirante agregó en su biografía de Wikipedia una fecha para su epitafio: 26 de noviembre de 2014 a las 16.45, justo cuando ella se estaba recuperando de una trombosis que la tuvo internada durante diez días. En otro octubre, pero de hace exactamente diez años, los tres muertos aparecidos en la pileta de un country en Las viudas de los jueves –con la que en 2005 ganó el Premio Clarín de Novela– la empujaron hasta este presente que hoy la ubica como una de las autoras más leídas y traducidas de la narrativa argentina actual, y una de las latinoamericanas con mayor proyección internacional. Todos sus muertos –los de aquel libro consagratorio y los que vendrían después– se multiplicaron en las versiones cinematográficas de sus novelas, incluido el reciente estreno de Tuya , un thriller doméstico que en orden cronológico marca la aparición de su primer cadáver literario.

O artigo completo em Claudia Piñeiro, la dama del suspenso