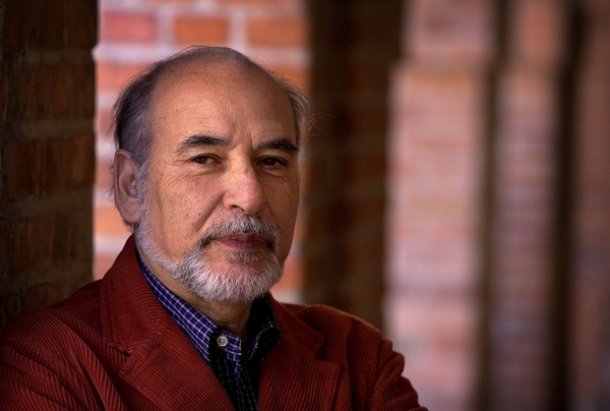

Tahar Ben Jelloun

Published21 Jun 2012

A Festa da Literatura e do Pensamento do Norte de África inicia-se a 22 de Junho com um debate em que participarão vários autores de blogs do Norte de África e Médio Oriente. Na impossibilidade de apresentar todos os autores e blogs fundamentais que são activistas fundamentais na cena política destas regiões vamos apresentar alguns.

Hoje, Tahar Ben Jelloun, de Marrocos.

TAHAR BEN JELLOUN (Marrocos, 1944) mudou-se para Paris em 1971 onde estudou filosofia e se tornou jornalista e escritor. Depois de vários romances, contos e poesia, recebeu o Prix Goncourt em 1987, por “La Nuit Sacrée”. Comprometido intelectual e culturalmente, nunca desistiu de lutar contra o racismo e a ignorância. A sua obra, tanto literária como intelectual, permitiu a aproximação das duas margens do Mediterrâneo transmitindo, ao ocidente, a cultura do mundo árabe.

Voice of the Maghreb

Brought up in Morocco, Tahar Ben Jelloun's imprisonment and exile shaped his poetry and fiction. Resident in Paris since 1971, he portrays the experience of the north African dispossessed.

While he was interned in Morocco under the iron fist of King Hassan II, Tahar Ben Jelloun found an escape in James Joyce. Books were not allowed but he asked his brother for the thickest paperback he could find, and the smuggled gift was a French translation of Ulysses. In captivity, he was fascinated "by this writer's liberty".

The young Moroccan composed his first poems, in French, during those 18 months in army camp, after his arrest in 1966 for taking part in student demonstrations in Casablanca. The experience was pivotal.

"At 21, I discovered repression and injustice - that the army would shoot students with real bullets," he says. He sought exile in Paris in 1971, and, now aged 61, is one of France's most fêted writers, and its most prominent author from the Maghreb. As well as poetry, fiction, plays and essays, he writes for France's Le Monde, Italy's La Repubblica and Spain's El País.

Much of his fiction is set in Morocco, though his main inspiration, Tangier - "where it's possible to see the Atlantic and the Mediterranean at the same time" - is "more a memory than a city". His novel The Sand Child (1985) probed the constraints on women in traditional Muslim society through the ambiguous tale of Ahmed/Zahra, a lamented eighth daughter passed off as a boy by her parents, who trades integrity and sanity for male privilege.

With its sequel, The Sacred Night (1987), he became the first north African to win the Prix Goncourt. Through the characters of women, migrants, prostitutes, the illiterate, the imprisoned, madmen and seers, he charts extreme states of powerlessness and invisibility, entrapment and rebellion, or, as he writes in his fictional meditation on ageing, Silent Day in Tangier (1990), of solitude "so absolute the self dissolves".

The Lebanese novelist Hanan al- Shaykh sees his "narrative acrobatics" as extending an Arabic tradition. The Sand Child borrows techniques from the oral storytellers of Marrakech's main square, the Jemaa El Fna. Describing his prose as "lyrical and delicate, forceful and questioning - a hypnotic mix of fable and modernity", she says, "it's never bitter polemic, but you can feel your hand forming a fist".

His youthful incarceration fed This Blinding Absence of Light (2001), a tour de force whose translation by Linda Coverdale (New Press/Penguin) won the 2004 Impac award and was shortlisted for this year's Independent foreign fiction prize. Based on the true story of a former inmate of Tazmamart, one of Hassan II's notorious desert prison camps, the novel reveals the fate of an officer accused of collusion in a failed coup and interred for 20 years in an underground cell, 3m by 1.7m, and only 1.7m high.

When, under international pressure, the political detainees were released in 1991, the few cadaverous survivors had lost inches off their height. "It's a book without concessions," says Ben Jelloun, who drew on a single three-hour interview with a survivor, Aziz Binebine. "I wrote it feverishly, bewitched by it, surprising myself with an inner strength."

The novel transforms unspeakable inhumanity into an existential tale of willed survival. Yet it took an unexpected toll on its author, who found himself accused by his collaborator of having stolen his story. For Ben Jelloun, it was a shock, since he maintains that he was approached to write the book by Binebine's brother, and signed a financial agreement to share the proceeds with Binebine, who approved a draft, and to whom the book was dedicated.

He feels let down by what he sees as the French media's readiness to believe the victim's word over the evidence. At book signings Moroccan protesters distributed leaflets urging people not to buy it.He has no regrets about the book, though, which he considers one of his best. He also found support from Hassan's successor, King Mohamed VI, whom he sees as a reformer, especially on women's rights.

The bruising controversy was the germ of The Last Friend (2004), a novel set in Tangier, in which the author alludes to his own spell in detention for the first time in fiction. A translation has just been published by the New Press, and Ben Jelloun will be in London to take part in the French Institute's Mosaïques festival, next Friday, and English PEN's international writers' day, Migrations of the Mind, at the Institute of Contemporary Arts on Saturday.

Ambiguous betrayal lies at the heart of The Last Friend. "Real friendship, like real poetry, is extremely rare - and precious as a pearl," Ben Jelloun says. Unspoken jealousy dogs a 30-year friendship, as Mamed, learning he has terminal cancer, breaks from Ali. The author works, listening to Mozart, in a light-filled attic a stone's throw from the former Left Bank haunts of Sartre and Camus.

He lives in Charenton, a suburb in eastern Paris, with his wife, Ayesha, the daughter of Moroccan Berbers, and their four children, aged from 19 to nine. Their 14- year-old son, who has Down's syndrome, is a "champion swimmer, who does theatre and music".

Ben Jelloun was born in Fez in 1944. The year before Moroccan independence from France in 1956, his family moved to Tangier, where he went to the French lycée. "My mother was illiterate. My father knew how to read but was a shopkeeper. We had a very modest life, with no music or books, except for the Koran."

In the French library of Tangier, he read copiously and discovered French poetry, but also the tension between cultural affinity and political oppression. When the Algerian war of independence broke out in 1954 there were many Algerians in Morocco, and older children went to join the FLN [National Liberation Front]. At the same time, he says, "pupils at the lycée were allied to the war for France. It was terrible".

As the Existentialists quarrelled over French policy in Algeria he admired Camus' writing but not his political views, "whereas I liked Sartre's views but not his writing". Tangier was an international city and Ben Jelloun met foreign writers passing through, including Samuel Beckett, Roland Barthes and the American Paul Bowles and his wife Jane.

"I didn't like Bowles, the man or the writer. He loved young Moroccan boys and preferred them illiterate. He'd write books in their words; it was an ambiguous relationship." He preferred the Beat poet Allen Ginsberg. "I asked him, 'why Tangier in the '50s?' He answered, 'boys and hashish - and neither is expensive'. But at least he was frank." Later, in Paris, Ben Jelloun became friends with Jean Genet, who taught him "about everything - writing, politics", and whom he depicted in a short story, "Genet and Mohamed, or the Prophet Who Woke Up the Angel".

Among his inspirations are Cervantes, who was influenced by Andalucian Arab culture; Matisse; and Fernando Pessoa ("I read a poem every night, as others read a prayer"). His own fiction was fed by scenes of injustice he witnessed in his youth. "The power of the word in Morocco belonged to men and to the authorities," he says. "No one asked the point of view of poor people, or women."

He studied philosophy at Rabat university, and, after his release from military camp in Ahermemon in 1968, taught for three years at schools in Tetuan and Casablanca, before the government decreed that philosophy be taught only in classical Arabic. That same year, 1971, the literary journal Souffles, for which he wrote, was banned, and he left for France.

In Paris he did a doctorate in social psychiatry, researching sexual impotence among north African migrants at a hospital. "I wasn't a doctor but a confidant," he says. "The wounds of migration hit me in the face: men who were psychologically destroyed. I'd thought sexuality was instinctive or natural, but it's profoundly linked to inner security and cultural context."

His insights fed the novel Solitaire (1976). He found himself cast by default as an interpreter between Europe and its migrants. He wrote of their cold welcome in the ironically titled French Hospitality (1984), and in Racism Explained to My Daughter (1998), cited a long "tradition of rejecting the foreign that reached a low point in the Dreyfus affair . . . Racism has not increased, but freed itself from shame".

He partly blames French assimilationism and unfinished colonial business from the Algerian war. He often talks to children in schools, and says the riots in French suburbs last November were "by kids born in France of foreign parents, saying we want to be considered 100 per cent French", yet ministers and media alike still brand them as immigrants.

His own career has been brushed by the tendency to exclude. While he sees himself as a "Moroccan writer of French expression", and says a writer's identity is defined by "language not nationality", as a French national he objects to being described as a francophone, rather than a French, writer.

In his post-9/11 book, Islam Explained (2002), he wrote that Islam is often "grasped only as a caricature", and he says, "the mistake we make is to attribute to religions the errors and fanaticism of human beings". Personally "incapable of mysticism" - though he respects the Sufi mystics - he is a secular Muslim, who believes "religion has to stay in the heart, not in politics. It is private".

In his latest novel, Partir, just out in French, Azel, a heterosexual Moroccan, has an affair with a gay Spanish man to gain a visa, but underestimates the toll on his sexuality and sense of self. "The question is, what are you ready to do to overcome poverty?" says Ben Jelloun.

"Emigration is no longer a solution; it's a defeat. People are risking death, drowning every day, but they're knocking on doors that are not open. My hope is that countries like Morocco will have investment to create work, so people don't have to leave."

Able to spend more time in Morocco now, he visits a seaside home in Tangier every two months. "In the 70s I was in exile; every time I went back I wondered if they'd take my passport away," he says. "But now, like those writers I admire - Joyce, Beckett, Genet - I feel only a metaphysical exile."

Tahar Ben Jelloun's inspirations: Don Quixote de la Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes Voyage to Tokyo by Yasujiro Uzo Piano Concerto no 16 in D, KV451 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart The Dance by Henri Matisse Poems by Fernando Pessoa .

in The Guardian.