A descolonização da educação no Uganda

Published28 Jul 2015

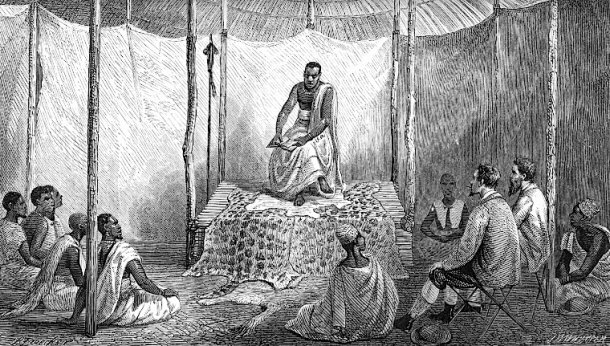

Pensadores e políticos do pós-colonialismo apostaram, em vários países africanos, na "descolonização da educação". Bwesigye bwa Mwesigire, advogado, escritor e académico ugandês, escreve sobre esta questão, invocando intelectuais como Edward Said ou Ngugi wa Thiong’o, focando-se no caso do Uganda.

My mother started her elementary education in the early to mid 1960s, a few years after Uganda attained independence. She has been a headmistress of various rural primary schools for a number of years now, so I ask her about the content of the education she received in the 60s and what pupils today receive. She tells me that they had textbooks that taught them about basic life in England, Canada and India among other places where the British had spread their tentacles. Little was said about us, she says. The textbooks would not have a photo/illustration of an African child/person. They read of things they would not find in their reality. The homes they saw in the books were far from the ones they lived in. Intentionally and unintentionally the image of a proper home became that of the English home.

Jamaica Kincaid, writing of her own experience as a student in a colonial school in Antigua says inOn Seeing England for the First Time:

“When I saw England for the first time, I was a child at school sitting at a desk. The England I was looking at was laid out on a map gently, beautifully, delicately, a very special jewel; it lay on a bed of sky blue – the background of the map – its yellow form mysterious, because though it looked like anything so familiar as a leg of mutton because it was England – with shadings of pink and green unlike any shadings of pink and green I had seen before, squiggly veins of red running in every direction. England was a special jewel all right, and only special people got to wear it. The people who got to wear England were English people. They wore it well and they wore it everywhere in jungles, in deserts, on plains, on top of the highest mountains, on all the oceans, on all the seas, in places where they were not welcome, in places they should not have been. When my teacher had pinned this map on the blackboard, she said, ‘This is England’ and she said it with authority, seriousness and adoration, and we all sat up. Is was as if she had said, ‘This is Jerusalem, the place you will go to when you die but only if you have been good.’ We understood then – we were meant to understand then – that England was to be our source of myth and the source from which we got our sense of reality, our sense of what was meaningful, our sense of what was meaningless – and about our own lives and much about the very idea of us headed that last list. At the time I was a child sitting at my desk seeing England for the first time, I was already familiar with the greatness of it.”

The almost complete decolonisation of Uganda’s primary education