Alejandro Zambra escreve sátira sobre acesso à faculdade no Chile

Published8 Jul 2015

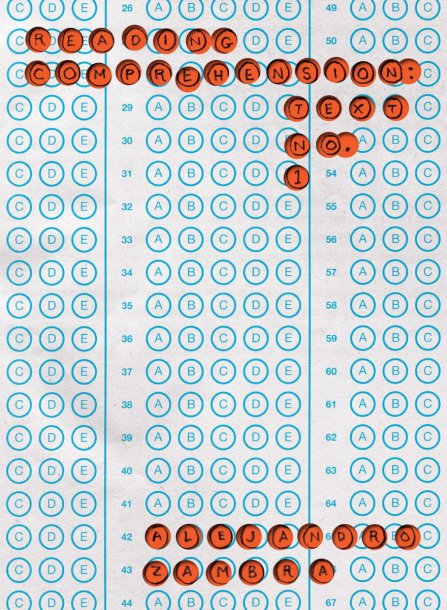

Ilustração: Matt Dorfman Alejandro Zambra, autor chileno que esteve no Próximo Futuro em 2014, publica texto inédito na revista The New Yorker, uma sátira aos exames de entrada para a faculdade no Chile.

After so many study guides, so many practice tests and proficiency and achievement tests, it would have been impossible for us not to learn something, but we forgot everything almost right away and, I’m afraid, for good. The thing that we did learn, and to perfection—the thing that we would remember for the rest of our lives—was how to copy on tests. Here I could easily ad-lib an homage to the cheat sheet, all the test material reproduced in tiny but legible script on a minuscule bus ticket. But that admirable workmanship would have been worth very little if we hadn’t also had the all-important skill and audacity when the crucial moment came: the instant the teacher lowered his guard and the ten or twenty golden seconds began.

At our school in particular, which in theory was the strictest in Chile, it turned out that copying was fairly easy, since many of the tests were multiple choice. We still had years to go before taking the Academic Aptitude Test and applying to university, but our teachers wanted to familiarize us right away with multiple-choice exercises, and although they designed up to four different versions of every test, we always found a way to pass information along. We didn’t have to write anything or form opinions or develop any ideas of our own; all we had to do was play the game and guess the trick. Of course we studied, sometimes a lot, but it was never enough. I guess the idea was to lower our morale. Even if we did nothing but study, we knew that there would always be two or three impossible questions. We didn’t complain. We got the message: cheating was just part of the deal.

O artigo completo aqui