Visões sobre a negritude na fotografia

Published14 Jul 2015

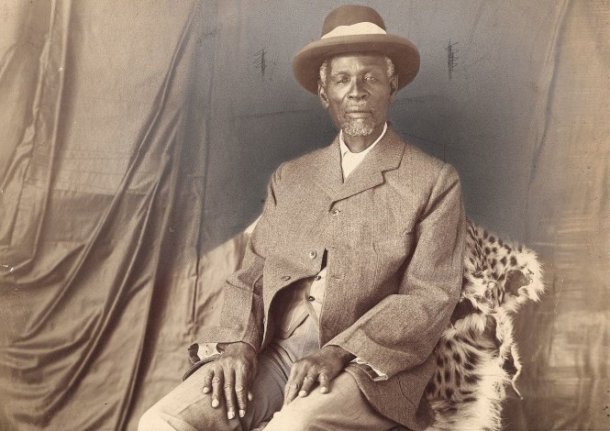

Imagem: Fotógrafo desconhecido, Retrato de estúdio do Rei Khama III. África do Sul, início do séc. XX

A exposição Distance and Desire: Encounters with the African Archive esteve patente no C/O Berlin, em colaboração com o African Photography from The Walther Collection. Elsa Guily, crítica de arte radicada em Berlim, analisa esta exposição, confrontando-a com outra, Genesis, de Sebastião Salgado, do ponto de vista da representação dos estereótipos e da perpetuação, ou não, da perspectiva ocidental dominante sobre a negritude.

Its eloquent title, Distance and Desire: Encounter with the African Archive, announces its preconceived purpose upfront: asking questions as to the role of archives and the impact of the photographic image in the writing of history. The project was organized into three sections, beginning with photographs from the Walther Collection and juxtaposing images from historical archives of photos taken in southern and eastern Africa around the turn of the twentieth century with works by contemporary artists from African perspectives whose approaches seek to reinterpret the ethnographic and colonial archive. From the outset, the visitor is clued in: it is impossible to view these photographs without realizing the violent relations inherent in European colonialism in Africa, and equally impossible to detach them from the historical contexts in which they were produced. The displacement of these archives invites us to examine our own gaze with a certain critical distance in order to reflect upon the processes of identifying and constructing difference, especially racial and gendered difference. The project re-envisions the archive as the bearer of collective memory, restoring the agency and individuality of the subjects portrayed and thereby creating alternative narratives of history.

In parallel to Distance and Desire, the Genesis project by photographer Sebastião Salgado intones an ecological message to humanity. These purportedly “socially conscious” photographs, which amount to a romantic invitation on an “eco-tourist” journey, perpetuate the representation of ethnicized bodies beside immaculate landscapes in black and white. The portraits’ subjects are made anonymous, their identities reduced to objectifying and vulgarizing captions that describe their practices and customs. Considering that both cultural visions are embedded in the same globalized, post-migratory space, it seemed to me that despite the Distance and Desire project’s noble intentions to deconstruct the white supremacist gaze, an ambivalent complicity might lodge in visitors’ minds. Thus I was compelled to interrogate both exhibition spaces jointly in light of the problems of images’ circulation and the act of “making visible.” How is the viewer positioned in relation to the discursive powers of representation? What relationships are formed between the photographer as an auteur, the individual photographed, and the viewer? At what point does the act of observation begin to dictate the subject’s development?

O texto completo em Gazing at a Distance